on

7 mins to read.

GloVE

The core concept of word embeddings is that every word used in a language can be represented by a set of real numbers (a vector). Word embeddings are N-dimensional vectors that try to capture word-meaning and context in their values. For example, the word “happy” can be represented as a vector of 4 dimensions [0.24, 0.45, 0.11, 0.49] and “sad” has a vector of [0.88, 0.78, 0.45, 0.91]. The reason for this transformation is so that machine learning algorithm can perform linear algebra operations on numbers (in vectors) instead of words. Word embeddings can be learned from text data and reused among projects. They can also be learned as part of fitting a neural network on text data.

Every word has a unique word embedding (or “vector”), which is just a list of numbers for each word. The word embeddings are multidimensional; typically for a good model, embeddings are between 50 and 500 in length. Similar words end up with similar embedding values because conceptually, if two words are similar, they should have similar values in this projected vector space.

A simple method is to represent each word using a one-hot encoded vector. Suppose your vocabulary contains 50,000 words, then the $n$th word would be represented as a 50K-dimensional vector, full of 0s except for a 1 at the $n$th position. However, with such a large vocabulary of 50K words, this sparse representation is very inefficient.

GloVe is one of the word embedding methods. It is an unsupervised learning algorithm for obtaining vector representations for words, developed by Stanford for generating word embeddings by aggregating global word-to-word co-occurrence matrix from a corpus. In other words, if two words co-occur many times, it means they have some linguistic or semantic similarity. It is an extension to the word2vec method.

GloVE is not used as much as the Word2Vec or the skip-gram models, but it has some enthusiasts in part of its simplicity. GloVE does not use a neural network architecture. GloVe stands for global vectors for word representation.

Given a corpus having $V$ words, the co-occurrence matrix $X$ will be a $V \times V$ matrix, where the $i$-th row and $j$-th column of $X$, $X_{ij}$ denotes how many times word $i$ has co-occurred with word $j$. An example is the co-occurrence matrix for the sentence “the cat sat on the mat” with a window size of 1 given as follows.

Simply put, GloVe allows us to take a corpus of text, and intuitively transform each word in that corpus into a position in a high-dimensional space. This means that similar words will be placed together.

How to get the vectors?

- GloVe: https://nlp.stanford.edu/projects/glove/

- Direct link: http://nlp.stanford.edu/data/glove.6B.zip

This zip file contains 4 files for 4 embedding representations.

After unzipping the downloaded file we find four txt files: glove.6B.50d.txt, glove.6B.100d.txt, glove.6B.200d.txt, and glove.6B.300d.txt. As their filenames suggests, they have vectors with different dimensions.

These dimensions are not interpretable. After being trained, the vector for a word with d dimensions capture many properties of that word. If the dimension is increasing, the vector can capture much more information but computational complexity will also increase.

We pick the smallest one with words represented by vectors of dimension 50 (glove.6B.50d.txt).

How to process the vector?

We need to parse the file to get as output: list of words, dictionary mapping each word to their id (position) and array of vectors

Note: you will need to replace glove.6B.50d.txt with the name of the text file you have chosen for the vectors if you want to use different dimensions.

So, I put the .txt file in a folder machine_learning_examples/large_files.

# load in pre-trained word vectors

print('Loading word vectors...')

word2vec = {}

embedding = []

idx2word = []

with open('machine_learning_examples/large_files/glove.6B/glove.6B.50d.txt', encoding='utf-8') as f:

# is just a space-separated text file in the format:

# word vec[0] vec[1] vec[2] ...

for line in f:

values = line.split()

word = values[0]

vec = np.asarray(values[1:], dtype='float32')

word2vec[word] = vec

embedding.append(vec)

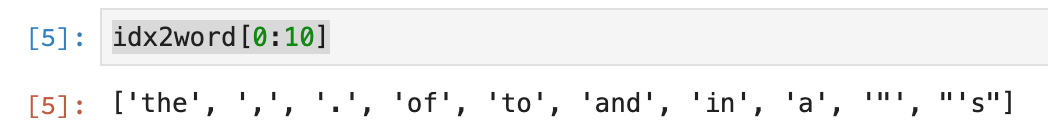

idx2word.append(word)For example, idx2word[0:10] will have the first 10 words in the list.

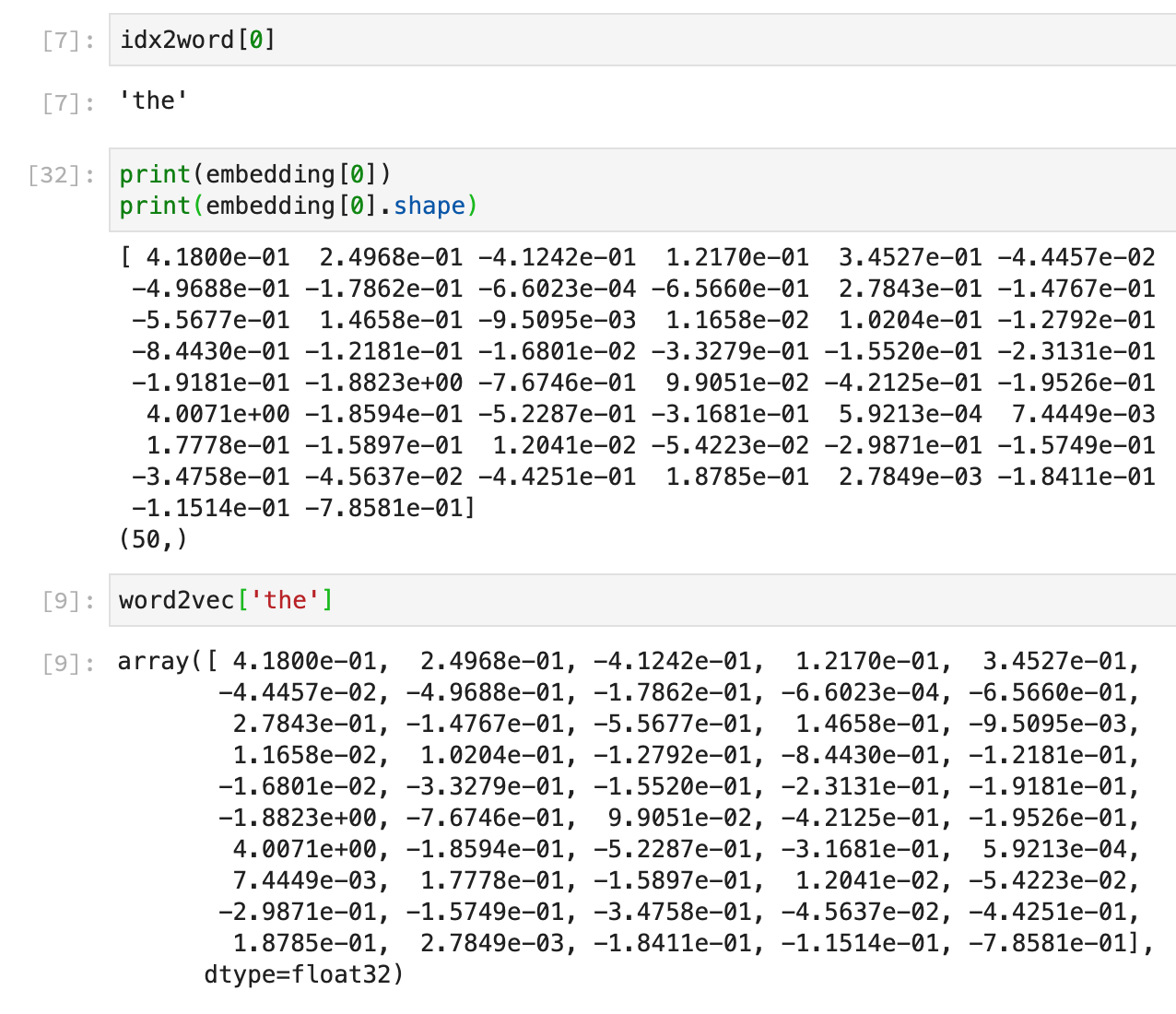

An example for the word ‘the’

If we printed the content of the file on console, we could see that each line contain as first element a word followed by 50 real numbers, meaning that that particular word is represented as 50 numbers.

For instance this is the first line, corresponding to token “the”:

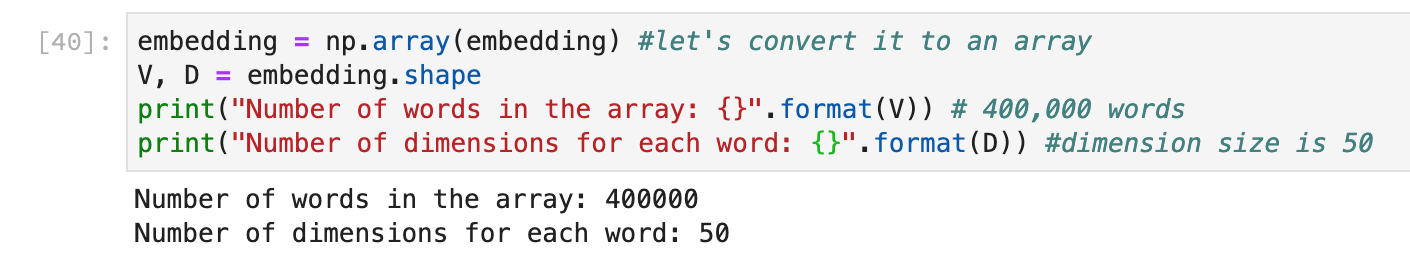

All the embeddings for 400,000 words represented in 50 dimensions

Let’s find similar words between king, man and woman

First, let’s check the representations of the words king, man and woman and whether they exist in GloVe.

print('king')

print(word2vec['king'])

print('\nman')

print(word2vec['man'])

print('\nwoman')

print(word2vec['woman'])

We will be using cosine distance.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import pairwise_distances

def dist1(a, b):

return np.linalg.norm(a - b)

def dist2(a, b):

return 1 - a.dot(b) / (np.linalg.norm(a) * np.linalg.norm(b))

# pick a distance type

dist, metric = dist2, 'cosine'

# dist, metric = dist1, 'euclidean'

king = word2vec['king']

man = word2vec['man']

woman = word2vec['woman']

v0 = king - man + woman

print(v0)

print(v0.shape)

Let’s find the distances between the vector v0 and all other vectors (which represent words) in the embedding and then sort them descending by the argument.

distances = pairwise_distances(v0.reshape(1, D), embedding, metric=metric).reshape(V)

#(400000,)

idxs = distances.argsort(axis=-1, kind='quicksort')[:4]

idxs

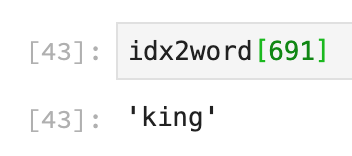

That means the vectors indexed by 691, 2060, 1131, and 1781 are similar to v0.

Let’s find out which words are those:

for idx in idxs:

word = idx2word[idx]

if word not in ('king', 'man', 'woman'):

print(word)The word indexed by 691 is ‘king’ so we exclude it. Therefore, the output is “queen”, “daughter” and “prince”.

Nearest Neighbors

We can also find the nearest neighbors of a word using similarity: