on

12 mins to read.

How to plot ROC curve and compute AUC by hand

Assume we have a probabilistic, binary classifier such as logistic regression.

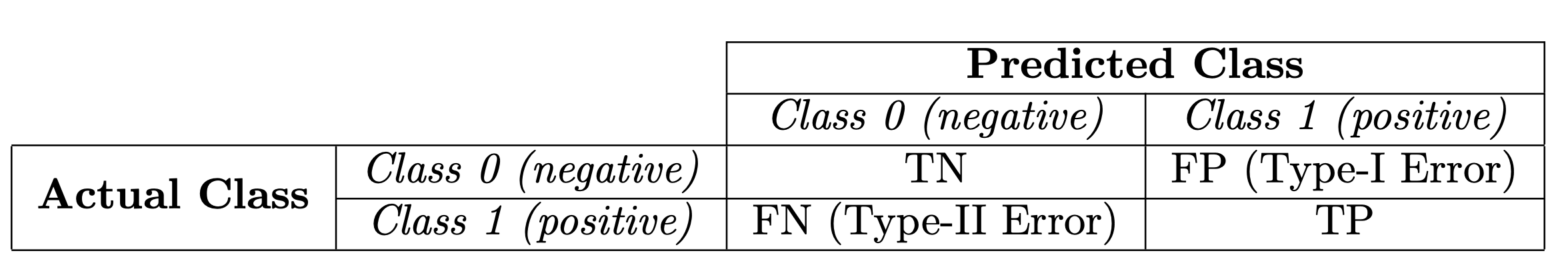

Before presenting the ROC curve (Receiver Operating Characteristic curve), the concept of confusion matrix must be understood. When we make a binary prediction, there can be 4 types of outcomes:

- We predict 0 while the true class is actually 0: this is called a True Negative, i.e. we correctly predict that the class is negative (0). For example, an antivirus did not detect a harmless file as a virus .

- We predict 0 while the true class is actually 1: this is called a False Negative, i.e. we incorrectly predict that the class is negative (0). For example, an antivirus failed to detect a virus.

- We predict 1 while the true class is actually 0: this is called a False Positive, i.e. we incorrectly predict that the class is positive (1). For example, an antivirus considered a harmless file to be a virus.

- We predict 1 while the true class is actually 1: this is called a True Positive, i.e. we correctly predict that the class is positive (1). For example, an antivirus rightfully detected a virus.

To get the confusion matrix, we go over all the predictions made by the model, and count how many times each of those 4 types of outcomes occur:

Since to compare two different models it is often more convenient to have a single metric rather than several ones, we compute two metrics from the confusion matrix, which we will later combine into one:

-

True positive rate (TPR), a.k.a. sensitivity, hit rate, and recall, which is defined as $\frac{TP}{TP+FN}$. This metric corresponds to the proportion of positive data points that are correctly considered as positive, with respect to all positive data points. In other words, the higher TPR, the fewer positive data points we will miss.

-

False positive rate (FPR), a.k.a. false alarm rate, fall-out or 1 - specificity, which is defined as $\frac{FP}{FP+TN}$. Intuitively this metric corresponds to the proportion of negative data points that are mistakenly considered as positive, with respect to all negative data points. In other words, the higher FPR, the more negative data points will be missclassified.

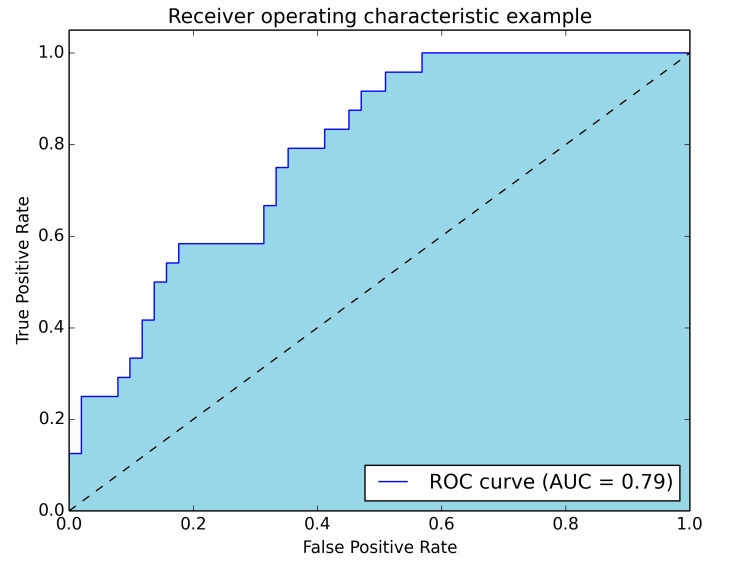

To combine the FPR and the TPR into one single metric, we first compute the two former metrics with many different threshold (for example $0.00, 0.01, 0.02, \cdots , 1.00$) for the logistic regression, then plot them on a single graph, with the FPR values on the abscissa and the TPR values on the ordinate. The resulting curve is called ROC curve, and the metric we consider is the AUC of this curve, which we call AUROC. Threshold values from 0 to 1 are decided based on the number of samples in the dataset.

AUC is probably the second most popular one, after accuracy. Accuracy deals with ones and zeros, meaning you either got the class label right or you didn’t. But many classifiers are able to quantify their uncertainty about the answer by outputting a probability value. To compute accuracy from probabilities you need a threshold to decide when zero turns into one. The most natural threshold is of course 0.5. Let’s suppose you have a quirky classifier. It is able to get all the answers right, but it outputs 0.7 for negative examples and 0.9 for positive examples. Clearly, a threshold of 0.5 won’t get you far here. But 0.8 would be just perfect.

That’s the whole point of using AUC - it considers all possible thresholds. Various thresholds result in different true positive/false positive rates. As you decrease the threshold, you get more true positives, but also more false positives.

The following figure shows the AUROC graphically:

AUC-ROC curve is basically the plot of sensitivity and 1 - specificity.

ROC curves are two-dimensional graphs in which true positive rate is plotted on the Y axis and false positive rate is plotted on the X axis. An ROC graph depicts relative tradeoffs between benefits (true positives, sensitivity) and costs (false positives, 1-specificity) (any increase in sensitivity will be accompanied by a decrease in specificity). It is a performance measurement (evaluation metric) for classification problems that consider all possible classification threshold settings.

In this figure, the blue area corresponds to the Area Under the curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC). The higher the area under the ROC curve, the better the classifier. The AUC has an important statistical property: the AUC of a classifier is equivalent to the probability that the classifier will rank a randomly chosen positive instance higher than a randomly chosen negative instance.

The diagonal line $y = x$ (dashed line) represents the strategy of randomly guessing a class. For example, if a classifier randomly guesses the positive class half the time, it can be expected to get half the positives and half the negatives correct; this yields the point (0.5, 0.5) in ROC space. It has an AUROC of 0.5. The random predictor is commonly used as a baseline to see whether the model is useful.

A classifier with an AUC higher than 0.5 is better than a random classifier. If AUC is lower than 0.5, then something is wrong with your model. A perfect classifier would have an AUC of 1. Usually, if your model behaves well, you obtain a good classifier by selecting the value of threshold that gives TPR close to 1 while keeping FPR near 0.

It is easy to see that if the threshold is zero, all our prediction will be positive, so both TPR and FPR will be 1. On the other hand, if the threshold is 1, then no positive prediction will be made, both TPR and FPR will be 0.

For example, let’s have a binary classification problem with 4 observations. We know true class and predicted probabilities obtained by the algorithm. All we need to do, based on different threshold values, is to compute True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Positive Rate (FPR) values for each of the thresholds and then plot TPR against FPR.

You can obtain this table using the Pyhon code below:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('ggplot')

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (16,9)

%matplotlib inline

score = np.array([0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2])

y = np.array([1,0,1,0])

# false positive rate

FPR = []

# true positive rate

TPR = []

# Iterate thresholds from 0.0 to 1.0

thresholds = np.arange(0.0, 1.01, 0.2)

# array([0. , 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1. ])

# get number of positive and negative examples in the dataset

P = sum(y)

N = len(y) - P

# iterate through all thresholds and determine fraction of true positives

# and false positives found at this threshold

for thresh in thresholds:

FP=0

TP=0

thresh = round(thresh,2) #Limiting floats to two decimal points, or threshold 0.6 will be 0.6000000000000001 which gives FP=0

for i in range(len(score)):

if (score[i] >= thresh):

if y[i] == 1:

TP = TP + 1

if y[i] == 0:

FP = FP + 1

FPR.append(FP/N)

TPR.append(TP/P)

# FPR [1.0, 1.0, 0.5, 0.5, 0.0, 0.0]

# TPR [1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.5, 0.5, 0.0]When you obtain True Positive Rate and False Positive Rate for each of thresholds, all you need to is plot them!

# This is the AUC

#you're integrating from right to left. This flips the sign of the result

auc = -1 * np.trapz(TPR, FPR)

plt.plot(FPR, TPR, linestyle='--', marker='o', color='darkorange', lw = 2, label='ROC curve', clip_on=False)

plt.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], color='navy', linestyle='--')

plt.xlim([0.0, 1.0])

plt.ylim([0.0, 1.0])

plt.xlabel('False Positive Rate')

plt.ylabel('True Positive Rate')

plt.title('ROC curve, AUC = %.2f'%auc)

plt.legend(loc="lower right")

plt.savefig('AUC_example.png')

plt.show()

To compute the area under curve for this example is very simple. We have two rectangles. All we need to do is to sum the areas of those rectangles:

\[0.5 \times 0.5 + 0.5 * 1 = 0.75\]which will give the AUC value.

Sci-kit Learn Approach

import numpy as np

from sklearn import metrics

scores = np.array([0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2])

y = np.array([1,0,1,0])

#thresholds : array, shape = [n_thresholds] Decreasing thresholds on the decision function used to compute fpr and tpr.

#thresholds[0] represents no instances being predicted and is arbitrarily set to max(y_score) + 1

fpr, tpr, thresholds = metrics.roc_curve(y, scores, pos_label=1)

#thresholds: array([1.8, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2])

#tpr: array([0. , 0.5, 0.5, 1. , 1. ])

#fpr: array([0. , 0. , 0.5, 0.5, 1. ])

metrics.auc(fpr, tpr)

#0.75RIEMANN SUM

However, this is not always that easy. In order to compute area under curve, there are many approaches. We can approximate the area under curve by summing the areas of lots of rectangles. It is clear that with hundreds and thousands of rectangles, the sum of the area of each rectangle is very nearly the area under curve. Our approximation gets better if we use more rectangles. These sorts of approximations are called Riemann sums, and they’re a foundational tool for integral calculus.

Let’s number the $n$ subintervals by $i=0,1,2, \ldots ,n−1$. Then, the left endpoint of subinterval number $i$ is $x_{i}$ and its right endpoint is $x_{i+1}$. We are imagining that the height of $f$ over the entire subinterval is $f(x_{i})$, the value of $f$ at the left endpoint. Since the width of the rectangle is $\Delta x$, its area is $f(x_{i})\Delta x$.

To estimate the area under the graph of $f$ with this approximation, we just need to add up the areas of all the rectangles. Using summation notation, the sum of the areas of all $n$ rectangles for $i = 0, 1, \ldots ,n−1$ is:

\[\text{Area of rectangles} = \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} f(x_{i}) \Delta x\]This sum is called a Riemann sum.

It can be defined in several different ways via left-endpoints, right-endpoints, or midpoints. Here we see the explicit connection between a Riemann sum defined by left-endpoints and the area between a curve and the x-axis on the interval $[a, b]$. If we used the value of $f$ at the right endpoint rather than the left endpoint, the result is the right Riemann sum.

The Riemann sum is only an approximation to the actual area underneath the graph of $f$. To make the approximation better, we can increase the number of subintervals $n$.

As we let $n$ get larger and larger (and $\Delta x$ smaller and smaller), the value of the Riemann sum (1) should approach a single number. This single number is called the definite integral of $f$ from $a$ to $b$. We write the definite integral as

\[\int_{a}^{b} f(x)dx = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} f(x_{i}) \Delta x\]Trapezoidal Rule

You now know that we can use Riemann sums to approximate the area under a function. Riemann sums use rectangles, which make for some pretty sloppy approximations. But what if we used trapezoids to approximate the area under a function instead?

By using trapezoids (aka the “trapezoid rule”) we can get more accurate approximations than by using rectangles (aka “Riemann sums”).